(this material is an excerpt from the book

"The Message of the Stones", by Dr. Javier Cabrera)

(EXCERPT #3A)

WHY STONE WAS USED

The conventional wisdom that man as an intelligent, thinking being only appeared

250,000 years ago leads inevitably to the mistaken notion that before this date, all

humanoid or humanlike beings were primitive, pre-human, incapable of intellectuality. It

should not surprise, then, that one objection to the contention that in a very remote past

a highly advanced humanity existed which recorded its messages for posterity on stone is

this: if the civilization was so advanced, why did it leave its mark in such a common,

primitive material as stone, rather than in some other medium more appropriate to the

society's technological achievements? Modern humanity, after all, threatened by nuclear

holocaust, is trying to conserve the most important scientific and technological knowledge

on microfilms placed in vacuum tubes which are then buried underground and covered with a

layer of concrete. It is on the surface a persuasive objection, since the linking of

primitive beings and stone carvings, used to record daily life and to pass time, is strong

in the popular imagination.

But this linking, and therefore the objection itself, are not justified. The scientific

and technological achievements of the people whose historical documents are the

gliptoliths flowed from the constant application of knowledge to the world around them.

Their intention was not to leave documents to glorify themselves, but to leave a series of

guideposts for future humanity, to show those who would come after them the ways that man

can dominate his environment, and to warn that any departure from the pursuit of knowledge

could cause regression to the level of animals, a level which could mean the extinction of

the human race. If we consider the information contained in some gliptoliths regarding

situations in the remote past which endangered human genus (see Chapter Six), the purposes

behind the leaving of testimonials become more meaningful: the way in which man can avoid

regression to the animal state and avoid extinction is through constant application of

knowledge. The question for gliptolithic man became how to ensure the survival of these

documents in a future they could not predict. Without spurning the use of other materials

(metal, ceramic, wood, textiles, lithic architecture, etc., as we will see), gliptolithic

man preferred to use stone. Stone had several advantages. First, it was abundant

throughout the world, and therefore would not the likely to be used as a commodity in

commerce. Second, stone would not run the risk of being oxidized like metal and would

better resist the passage of time with engravings intact. Though they had dominated their

environment, they knew it was likely that future men would not know how to control

geological upheavals that might destroy the stones. For this reason, and also to protect

the stones from the effects of nature (atmospheric gases, rain, heat, cold, radiation,

etc.) they decided to protect them in excavated deposits in the most stable regions of the

planet. And they took other precautions: they did not modify the nature shaped of the

stone, so that it retained its resistance; and they buried the stones in sand so they

would not rub up against each other. It is thus that after these remote past, the engraved

stones are beautifully preserved.

OTHER MATERIALS WITH GLIPTOLITHIC WRITING

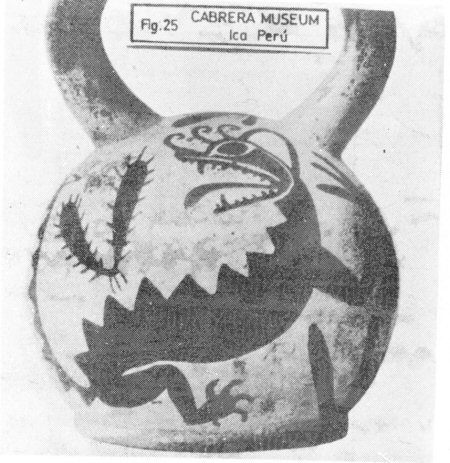

If we compare the designs on the

gliptoliths with those on other ancient objects of porcelain, ceramic, wood, and

cloth, scattered throughout the world, there is no doubt that gliptolithic nan

also used these materials to leave his messages. There are figures representing

fabulous animals which closely resemble many of those the paleontologists tell

as lived in the remote past, such as the dragons on Chinese porcelain, a

mythical animal but at the same time quite like the pterodactyl (winged

dinosaur). Another example is the figure of a stegasaurus on a ceramic found in

a tomb pertaining to the Pachacanac culture (a Pre-Incaic society) to the south

of

Lima

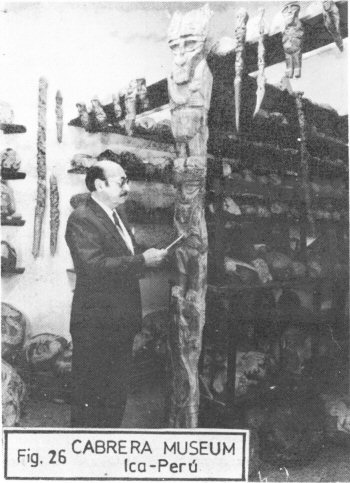

(Fig. 25). Similarly, we have the carved wood objects found in the desert to the

south of Ocucaje, lea, in which various prehistoric animals are depicted, one of

which shows dinosaurs (Fig. 26) as well as human figures. In others the figures

and designs reveal aspects of the scientific and technological achievements of

gliptolithic man, as for example, the symbolic representation of the technology

of space flight in many ceramics found in tombs from the Nasca culture (Pre-Incaic)

in the department of Ica (see illustrations in Chapter 9); also the symbolic

representations made in numerous Paracas cloths (Pre-Incaic culture) in the

department of Ica, which reveal a profound understanding of human microphysical

biology (see Chapter Seven, figure of Paracas cloth). In one Mochica (Pre-Incaic)

ceramic we can see the different phases through which an animal passed before it

was fully developed. There is no doubt that the animal in question is the

stegasaurus and that the phases are metamorphic phases. This further documents

that man coexisted with the dinosaur, that the latter was not hatched fully

developed (unlike paleontology teaches), and that man was a being so far evolved

that the possessed knowledge of biology (see figure previous page).

FIGURE 25: Ceramic with figure of

stegasaurus. The ceramic was found to the south of the city of Lima in a

Pachacamac (Pre-Incaic) tomb.

For this reason archeologists attribute the figure to the imagination of the

Pachacamac people, but it belongs in fact to the gliptolithic culture.

FIGURE 26: One of the many wood

objects that come from the south of Ocucaje, Ica.

This one reveals an aspect of the reproductive cycle of the dinosaur, knowledge

possessed by gliptolithic man.

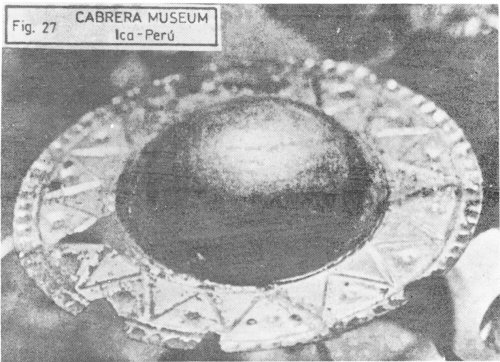

I also think that gliptolithic man

left messages in sheets of metal resistant to time, such as gold and silver. The

unusual sheets of gold found in

Ecuador

whose designs resemble those the gliptoliths, provide evidence for

this hypothesis. These sheets form part of the collection

of

Father Carlo Crespi, and are housed in the Church of

Maria Auxiliadora, in Cuenca, Ecuador (Fig.

27).The

sheets

have not been dated. It is possible that gliptolithic humanity

knowing that man might have to avoid the end of his

existence by reverting to an animal state in which the instinct of egoism would

flourish, may have feared that man would then care less about figures and

symbols than about the material in which the

figures and symbols appeared. It is also possible that sheets of some unknown

material may have been used, but the same fear about the acceptance

of the messages would have prevailed. I think that gliptolithic man thought to

counteract the acquisitive instinct of future men by inscribing messages not on utilitarian

objects but on objects of beauty, as if they were adornments or decorations, so

that man would be more likely to value them and conserve them, and they could

one day be interpreted and understood for what they are. Thus

gliptolithic humanity engraved messages on

different types of silver ware, tools, and a variety of objects, preferably

of gold and silver, whose shape and designs even today are the subject of

ingenious and sometimes arbitrary interpretations.

Such is true in the case of the well-known turns of gold with

incrustations of precious stones, and the

tumis made from a very durable material called champi

(a

combination of gold, silver and copper, although the

bonding technique is unknown), found in Inca

and Pre-Inca tombs.

FIGURE 27: One of the unusual

sheets of gold found in Ecuador, whose origin has not been determined by

archeologists.

It was made by gliptolithic humanity and is today part of a collection which

Father Carlo Crespi keeps in the

Church of Maria Auxiliadora in Cuenca, Ecuador. Photo published in The Gold of

the Gods by Erich von Daniken.

Archeologists insist that these tumis were made by Inca or Pre-Inca men and they

think that they were used in ceremonial rites and as surgical instruments. But

the gold tumis with precious stones and the

tumis made of charapi were made by gliptolithic humanity, and the designs are

nothing but symbols amenable to deciphering (see Chapter

Five).

BACK TO EXCERPT INDEX